I love Sardinia. It is an island of extraordinary natural and cultural richness in the heart of the Mediterranean (I’m working on an ecocritical long read on mare nostrum).

Islands are places where it is easier to come into contact with Thing Power, with the force of matter—but Sardinia holds a power of its own, in a massive concentration.

I’m used to writing so that things may reveal their secrets to me, like the stones of the dry-stone walls, locked in a wise balance by hands long vanished in time. Sardinia is a book that is hard to penetrate, and hard to scratch. You try to enter it, but instead, it overtakes you.

Sardinia is the stone pulled down from a nuraghe, an oracle of a remote geology. In its chiselled form, shaped to be laid—one beside another, one atop the next—to shield against the wind or the beasts, the stone holds time within it. It clings tightly to the Mediterranean scrub that caresses it, slipping through the cracks, almost dissolving into it. Here, the stones seem to lose their ancient inanimate nature, revealing themselves in the form of vegetation unknown to us—akin to myrtle or mastic, to capers or blackberries, among the agave, prickly pears, and olive trees—blending their scent with these wild essences, carried and scattered all around by the mistral blowing fiercely from the sea.

The wind is the voice of these stones; to it, they entrust the stories they have witnessed. And under the sun, I sit and listen. They have a vibrant sound—you must become almost animal to perceive it, so subtle it teeters on the edge of the audible. They chirr, they neigh, they grunt and whisper verses, words, distant echoes of cries—of joy and war, of breath held in fear of the night, and of wonder at the stars, which only a shepherd, confessing his dreams to his flock beneath a tree, could attempt to count.

They are voices of servants, of kings, of women at the doorstep or by the well, of soldiers—everyone is, sooner or later, a traveller. And from far away, across space and time, they have come here, to Sinis, at the centre of the Mediterranean. Here, one arrives chasing the sun as it hides in the west, drawn forward by the promise that with every step, a ray of fleeing light might still be captured before vanishing with time. Here, you hear the footsteps of legions of men pressing into the earth after endless days at sea, and like them, the sand slipping through your fingers and the sight of green and stone houses—scattered across the dunes or perched, sparse, on the hills to the east—brings comfort.

Perhaps that is why, once you leave the Island, you must return. Perhaps that is why the Island is both harbour and prison, why stone—raw or carved—is soul, life, and vegetation.

This deep connection stretches far back for me, to a time when I was a child. I first discovered Sardinia in books, especially in a great book—now somewhat forgotten—that my mother had me read.

Only now do I realize its significance also from an ecocritical perspective. And so here is the first outline of the Ecocritical issue we can find in Padre padrone by Gavino Ledda.

It is an autobiographical novel about his struggle for emancipation from a harsh, authoritarian father in rural Sardinia. Forced to leave school as a child to work as a shepherd, Gavino grows up in isolation, subjected to his father’s strict control. Over time, he discovers a passion for language and education, which becomes his path to freedom. Music, especially playing the flute, serves as his first means of self-expression and connection to nature. Eventually, he breaks free, enlists in the military, and pursues higher education, transforming himself from an illiterate shepherd into a scholar. The novel is a powerful reflection on oppression, personal growth, and the transformative power of knowledge.

The narrative of Gavino Ledda allows us to explore the profound connection between nature and the socio-cultural conditions depicted in the novel. This approach highlights how the natural environment of Barbagia is not merely a static backdrop but an active and significant element in shaping the protagonist's experiences and identity.

Gavino himself and his language are a sort of medium between nature and evolving society and culture. Every kind of language, word as well sound, literature, and music.

Gavino wants to learn the read and write, to speak Italian, and correctly write, and the language he acquires is not just a tool for emancipation but one deeply rooted in nature, especially in its sounds. Music plays a crucial role in the novel and, for the protagonist, it is not only a symbol of elevation and culture but also a unique code that gives meaning to a nature that is far from mute. During his nights as a shepherd, nature spoke to his heart and all his senses, and he was able to converse with it by playing the flute.

Music as metalanguage.

Music for Gavino is the bridge from nature to culture. A meta or pre-spoken language that makes emotion manageable.

It represents a shift from isolation to self-expression, from oppression to personal discovery.

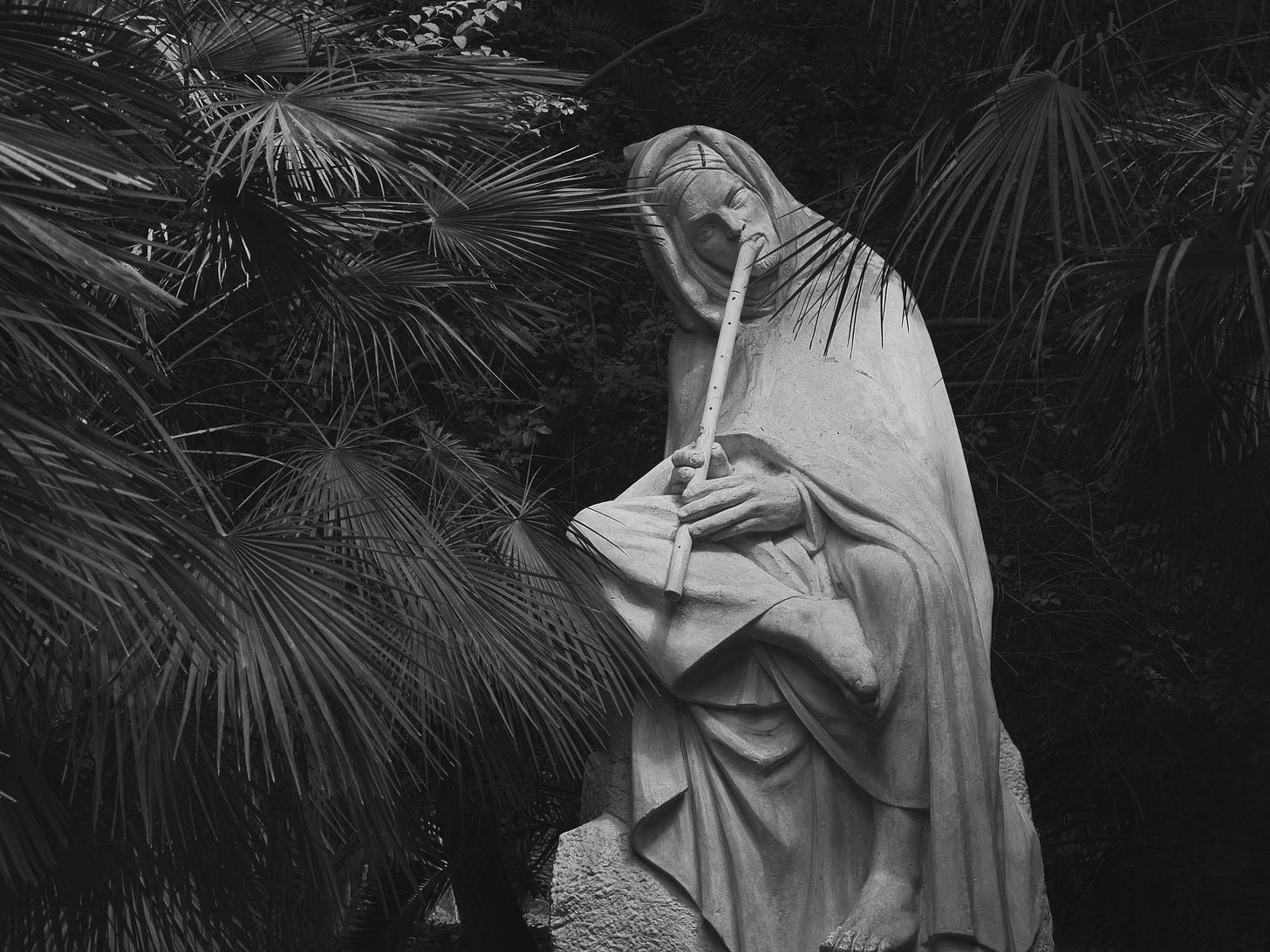

The flute becomes his first real voice, a way to break the silence of his isolation.

Unlike the rigid commands of his father, music is fluid, creative, and personal.

It symbolizes intellectual and emotional liberation, foreshadowing his later pursuit of education. But is also a Connection to Nature.

He listens to the sounds of the wind, animals, and landscape, turning them into a form of rhythm and melody.

His flute-playing is not just an artistic act but a dialogue with nature.

Nature, which at first represents a prison, transforms into a source of inspiration and connection.

Also from an esthetic point of view, the lightness of sounds is sharply contrasted with the brutal, authoritarian language of Gavino’s father.

The father’s speech is always harsh, directive, and absolute; it leaves no space for self-expression.

Music, in contrast, is free-flowing and open-ended, allowing Gavino to explore emotions and identity beyond his father’s control.

His ability to create music foreshadows his eventual escape from his father’s oppressive rule and his journey toward self-determination.

Music is also a Symbol of Education and Cultural Growth

As Gavino grows older and gains access to formal education, music becomes a metaphor for learning and knowledge.

Just as he teaches himself to play the flute, he later learns to read and write, using language as another form of liberation.

Music, like education, allows him to transcend the limitations of his upbringing and connect with a broader world.

His journey from an illiterate shepherd to a scholar is mirrored by his ability to create music, turning sound into meaning just as he turns words into knowledge.

Music is a transformative force, it is an agent. It ironically represents a ‘silent rebellion’ against oppression and a means of reclaiming his voice in a world that sought to silence him.

The other transformative agent is nature.

Nature as Both Cage and Refuge

The rural Sardinia described by Ledda is a harsh, arid, and wild land, symbolizing isolation and oppression. For young Gavino, the landscape represents a prison: his forced labour as a shepherd, imposed by his father, ties him to a hostile environment with no escape routes. At the same time, nature also serves as a primordial refuge, a place where the protagonist discovers himself, developing an intimate connection with the natural world around him. So the conflict with his father becomes the conflict of the Man for the Domination of Nature.

The novel emphasizes the relationship of dominance that the father exerts not only over his son but also over the environment. This control manifests through the use of nature for sustenance and power, highlighting an exploitative rather than harmonious relationship. The pastoral life is depicted as a constant struggle against natural forces, a metaphor for the patriarchal power that seeks to bend both nature and Gavino to its will.

Education and Overcoming the Environment

The protagonist’s emancipation is also achieved through his distancing from the natural environment. Literacy and exposure to the cultural world enable him to surpass the limitations imposed by both his father and the landscape. However, this detachment does not lead to a complete rejection of nature: Gavino recognizes the beauty and primal strength of Sardinia’s landscape but understands that true freedom requires a balance between culture and nature. Nature is a Symbol of Identity

Barbagia, with its rugged and unspoiled landscapes, represents Sardinia’s cultural and historical identity. The detailed depiction of the territory reflects the soul of a community inseparably linked to the land yet also trapped by this relationship. Even as Gavino emancipates himself, he never fully renounces this identity, acknowledging that the nature of his homeland has shaped his character and worldview.

Ecocritical Perspective

From an ecocritical standpoint, Padre padrone can be read as a narrative exploring the tension between anthropocentrism and ecocentrism. Patriarchal domination and environmental control represent an anthropocentric paradigm that the protagonist seeks to break. Reconciliation with nature, through awareness and education, suggests the possibility of a new equilibrium, where human beings recognize their interdependence with the natural world.

In Padre padrone, nature is much more than a mere setting: it is a living force that influences the characters’ destinies and a symbol of the protagonist’s internal and external struggles. The ecocritical analysis highlights how Ledda’s novel serves as a profound reflection on the relationship between humans and their environment—a theme that, though rooted in a specific context, resonates universally in the contemporary era.

A deeper dive into the character’s voice

analyzing the language of the novel with Sentiment Analysis (with the same framework used for Conrad Series)

From an ecocritical perspective, we can clearly see how the language of the two main characters—Gavino and his father—reflects not only their power struggle but also their relationship with nature and the surrounding environment. The novel narrates a generational and cultural conflict in which nature serves both as a prison and a space for emancipation.

The Father’s Language: Domination and Brutality

Gavino’s father employs a harsh, authoritarian, and often violent form of speech. His communication is minimal, reduced to orders and the imperatives of pastoral life. This language reflects his worldview, in which nature (and Gavino seems to be treated as any of his sheep) is something to be bent to human will, just as his son must be dominated to become a man according to patriarchal traditions. The results:

Emotional tone: aggressive, rigid, coercive.

Relationship with nature: instrumental and exploitative; the land and animals exist to be used.

Lexicon: concrete, sparse, tied to material necessities (herding, toil, obedience).

Gavino’s Language: Evolution and Awareness

Gavino, on the other hand, undergoes a linguistic evolution. In the beginning, his mode of expression is limited, almost imprisoned by his isolation. As he discovers language and culture, his words become richer, more reflective, and poetic. Nature, initially a prison, transforms into a space of revelation and knowledge. He moves from sound of the nature to music to words. The results:

Emotional tone: initially frustrated and oppressed, later increasingly aware and lyrical.

Relationship with nature: from obstacle to source of inspiration and understanding of the world.

Lexicon: at first elementary and concrete, later more abstract and philosophical.

Nature as a Mirror of Conflict

Nature is never a mere backdrop. It mirrors the conflict between father and son. The harsh Sardinian landscape, the relentless wind, and the dry-stone walls symbolically represent both the harshness of the life imposed by the father and the possibility of resistance and change. For Gavino, it becomes a place of learning and transformation.

Overall Sentiment Analysis

Predominant emotions: oppression, anger, fear, later hope and liberation.

Linguistic dynamic: authoritarian and pragmatic language of the father vs. Gavino’s evolving and poetic language.

Ecocritical tone: a critique of the use of nature as a tool of control, but also a celebration of the possibility of a more harmonious relationship with the environment through knowledge and education.

From the Sentiment Analysis, some main trends emerge:

Negativity: The text is permeated by a sense of oppression, frustration, and fear, especially in the moments when Gavino describes his relationship with his father, who is authoritarian and often violent. Nature, although initially defined with a certain sense of wonder, also becomes a place of isolation and suffering for Gavino, especially when he is forced to work as a shepherd under harsh conditions.

Positivity: Despite the difficult context, there are moments of positivity, particularly when Gavino describes the beauty of nature, his bond with animals (such as the dog RusigabŔdra), and the moments of freedom he manages to find in the solitude of the Sardinian landscape. These moments are often accompanied by a sense of peace and connection with the environment.

Neutrality: There are also neutral descriptive passages, especially when Gavino details daily activities such as milking sheep or tending to the flock. These moments reflect a routine that, although exhausting, is accepted as part of life.

The negative tone is higher during moments of conflict with the father and during moments of isolation.

The positive tone increases during descriptions of nature and moments of freedom.

The neutral tone remains constant during descriptions of daily activities.

The quantitative analysis does not reflect the dynamics identified by the qualitative one. Likely, the NLTK libraries used for sentiment analysis in the Italian language are not that accurate. The Pie chart describes the language as neutral.

Emotive and Descriptive Language: Gavino describes nature with a language rich in sensory details, highlighting the beauty and grandeur of the Sardinian landscape. He uses metaphors and similes to depict the scenery, such as when he speaks of the "summer snowfall" of locusts or the "speaking silence" of nature. This language reflects a deep emotional connection with the environment, which becomes a refuge for him from the harshness of daily life.

Language of Isolation and Loneliness: Gavino also portrays nature as a place of solitude, especially when he is forced to work alone. He uses words like "silence," "isolation," and "fear" to describe the moments when he feels abandoned and vulnerable.

In conclusion, Padre padrone narrates a struggle for social and cultural emancipation and the transition from an anthropocentric, dominative view of nature to a more conscious and respectful perspective on the environment.

Methodology and Tools Used in the Analysis

1. Methodology

The sentiment and language analysis was conducted following a structured methodology, which includes the following steps:

Text Preprocessing:

Text cleaning: Removal of special characters, punctuation, and numbers.

Tokenization: Splitting the text into words or sentences (tokens).

Stopword removal: Elimination of common words that do not add semantic value (e.g., "and", "the", "a").

Lemmatization: Reducing words to their base form (e.g., "running" → "run").

Sentiment Analysis:

Sentiment classification: Using a machine learning model or a predefined lexicon to classify each sentence or paragraph as positive, negative, or neutral.

Metric calculation: Counting the occurrences of positive, negative, and neutral sentiment.

Result visualization: Creating charts to represent the distribution of sentiment in the text.

Language Analysis:

Keyword extraction: Identifying the most frequent and significant words in the text.

Frequency analysis: Calculating the frequency of words and phrases to identify main themes.

Metaphor and simile analysis: Identifying rhetorical devices used to describe nature and the environment.

Character Comparison:

Text segmentation: Dividing the text into parts attributable to each character.

Comparative analysis: Comparing the language and sentiment between the two main characters.

2. Tools Used

The following tools and libraries were used to conduct the analysis:

Python: The primary programming language for text analysis.

Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK): A Python library for text preprocessing (tokenization, stopword removal, lemmatization).

TextBlob: A Python library for sentiment analysis.

Matplotlib and Seaborn: Python libraries for data visualization (bar charts, pie charts, etc.).

WordCloud: A Python library for creating word clouds.

3. Code for the Analysis

Here is an example of Python code AI-generated to conduct sentiment and language analysis on a text file:

# Importing necessary libraries

import nltk

from textblob import TextBlob

import pandas as pd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from wordcloud import WordCloud

from nltk.corpus import stopwords

# Downloading necessary NLTK resources

nltk.download('punkt')

nltk.download('stopwords')

nltk.download('wordnet')

nltk.download('vader_lexicon')

# Load Italian stop words

stop_words = set(nltk.corpus.stopwords.words('italian'))

# Function for text preprocessing

def preprocess_text(text):

# Tokenization

tokens = nltk.word_tokenize(text)

# Stopword removal

filtered_tokens = [word for word in tokens if word.lower() not in stop_words]

# Lemmatization

lemmatizer = nltk.WordNetLemmatizer()

lemmatized_tokens = [lemmatizer.lemmatize(word) for word in filtered_tokens]

return lemmatized_tokens

# Function to save lemmatized text to file

def save_lemmatized_text(tokens, output_path):

with open(output_path, 'w', encoding='latin-1') as file:

file.write(' '.join(tokens))

# Function to analyze sentiment of text

def analyze_sentiment(text):

blob = TextBlob(text)

sentiment = blob.sentiment

return sentiment.polarity

# Function to analyze sentiment of each sentence

def analyze_sentiment_per_sentence(sentences):

sentiment_data = []

for sentence in sentences:

polarity = analyze_sentiment(sentence)

sentiment_data.append((sentence, polarity))

return sentiment_data

# Function to create wordcloud for most frequent words

def create_wordcloud(words, title="Word Cloud"):

wordcloud = WordCloud(width=800, height=400, background_color='white').generate(' '.join(words))

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 5))

plt.imshow(wordcloud, interpolation='bilinear')

plt.axis('off')

plt.title(title)

plt.show()

# Function to classify sentiment (positive, negative, neutral)

def classify_sentiment(score):

if score > 0:

return "Positive"

elif score < 0:

return "Negative"

else:

return "Neutral"

# Function to generate a pie chart of sentiment distribution

def sentiment_pie_chart(sentiment_counts):

labels = sentiment_counts.keys()

sizes = sentiment_counts.values()

plt.figure(figsize=(6, 6))

plt.pie(sizes, labels=labels, autopct='%1.1f%%', startangle=140)

plt.title('Sentiment Distribution')

plt.show()

# Function to load the text from a file

def upload_file(file_path):

with open(file_path, 'r', encoding='latin-1') as file:

text = file.read()

return text

# Main function to perform all the tasks

def analyze_file(file_path, nature_keywords=None):

text = upload_file(file_path)

sentences = nltk.sent_tokenize(text)

# Preprocess text (remove stop words, lemmatize)

lemmatized_tokens = preprocess_text(text)

# Save lemmatized text to file

save_lemmatized_text(lemmatized_tokens, 'lemmatized_text.txt')

# Analyze sentiment of each sentence and store in DataFrame

sentiment_data = analyze_sentiment_per_sentence(sentences)

sentiment_df = pd.DataFrame(sentiment_data, columns=['Sentence', 'Polarity'])

# Save sentiment data to file

sentiment_df.to_csv('sentiment_data.csv', index=False)

# Sentiment analysis for pie chart

sentiment_counts = {'Positive': 0, 'Negative': 0, 'Neutral': 0}

for _, polarity in sentiment_data:

sentiment_class = classify_sentiment(polarity)

sentiment_counts[sentiment_class] += 1

# Plot the pie chart of sentiment distribution

sentiment_pie_chart(sentiment_counts)

# Word Cloud for the most frequent words in the text

create_wordcloud(lemmatized_tokens, title="Word Cloud of Most Frequent Words")

# Word Cloud of Nature-related words

nature_words = [word for word in lemmatized_tokens if word in nature_keywords]

create_wordcloud(nature_words, title="Word Cloud of Nature-Related Words")

# Word Cloud for Positive and Negative Words

positive_words = [word for word in lemmatized_tokens if analyze_sentiment(word) > 0]

negative_words = [word for word in lemmatized_tokens if analyze_sentiment(word) < 0]

create_wordcloud(positive_words, title="Word Cloud of Positive Words")

create_wordcloud(negative_words, title="Word Cloud of Negative Words")

# Sentiment plot analysis (scatter plot)

plt.figure(figsize=(10, 6))

plt.scatter(sentiment_df.index, sentiment_df['Polarity'], c='blue', alpha=0.5)

plt.axhline(0, color='gray', linestyle='--')

plt.title('Sentiment Analysis Plot')

plt.xlabel('Sentence Index')

plt.ylabel('Polarity')

plt.show()

# Example usage

# Define nature-related keywords (you can expand this list)

nature_keywords = ["natura", "albero", "cielo", "terra", "fiume", "mare", "montagna", "piante", "animale"]

# Path to your text file

file_path = r"padre_padrone.txt" # Replace with the correct file path

analyze_file(file_path, nature_keywords)

4. Instructions for Uploading the File

To run the analysis on a text file, follow these steps:

File preparation:

Ensure the text file is in

.txtformat and encoded in latin-1.Save the file with an appropriate name, such as

padre_padrone.txt.

Code execution:

Copy the Python code into a

.pyfile or run it directly in a Python environment (e.g., Jupyter Notebook).Modify the

file_pathvariable with the path to the text file you want to analyze.Run the code.

Result visualization:

The code will generate a pie chart showing the sentiment distribution (positive, negative, neutral).

A WordCloud will also be generated, displaying the most frequent words in the text, those related to nature and those that reveals positive and negative sentiment.